Short answer (at least for me): when growers use your research.

Before I was involved in applied research, I had a startling realization: IPM is difficult. We live in high-input world where agricultural production has been spatially and managerially consolidated. While we could probably bicker about the benefits and/or detriments about this development, it doesn’t necessarily change our reality, this is what modern agriculture looks like. Furthermore, it shouldn’t change our goal: improve integrated pest management. One of the greatest challenges we face in accomplishing this goal is the implementation of integrated pest management. And by “implementation” I ultimately mean: How many growers are actually using our research? In this article, we examined the grower adoption of insecticide resistance management practices in onion through an extension-based scouting program. Spoiler alert: it worked.

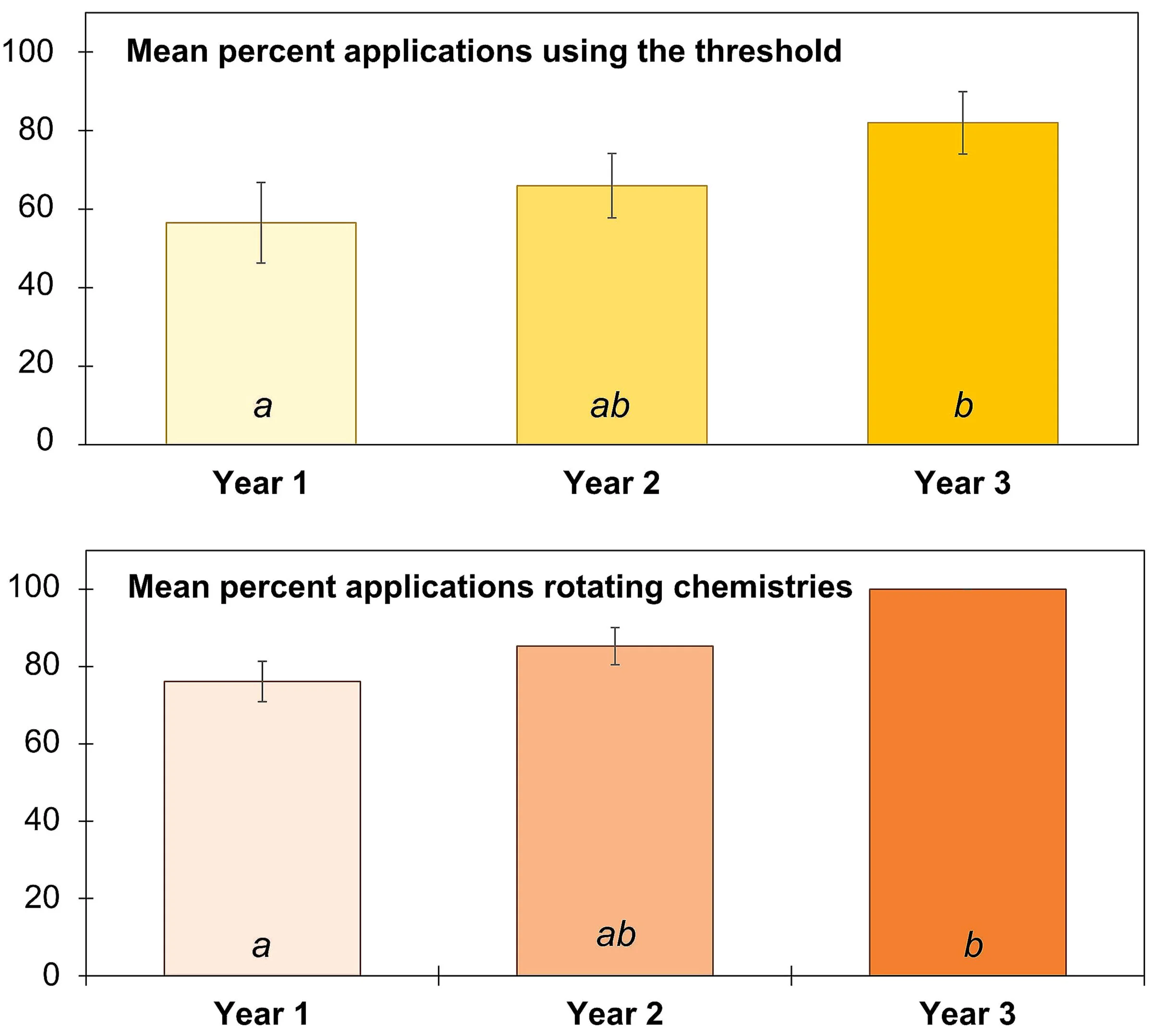

Adoption of insecticide resistance management tactics to manage onion thrips for growers who participated in our program over three years in New York. The average percentage of insecticide applications made using the action threshold of one thrips per leaf (above), and the percentage of insecticide applications rotating between insecticide classes (below). The scouting program was voluntary and growers could choose whether or not to follow the scouting recommendation of using the action threshold and rotating between insecticide classes.

Abstract

Background: Insecticide resistance management (IRM) practices that improve the sustainability of agricultural production systems are developed, but few studies address the challenges with their implementation and success rates of adoption. This study examined the effectiveness of a voluntary, extension-based program to increase grower adoption of IRM practices for onion thrips (Thrips tabaci) in onion. The program sought to increase the use of two important IRM practices: rotating classes of insecticides during the growing season and applying insecticides following an action threshold.

Results: Onion growers (n = 17) increased their adoption of both IRM practices over the 3-year study. Growers increased use of insecticide class rotation from 76% to 100% and use of the action threshold for determining whether to apply insecticides from 57% to 82%. Growers who always used action thresholds successfully controlled onion thrips infestations, applied significantly fewer insecticide applications (one to four fewer applications) and spent $148/ha less on insecticides compared with growers who rarely used the action threshold. Growers who regularly used action thresholds and rotated insecticide classes did so because they were primarily concerned about insecticide resistance development in thrips populations.

Conclusion: Implementation of the IRM education program was successful, as adoption rates of both practices increased within 3 years. Growers were surprisingly most receptive to adopting these practices to mitigate insecticide resistance as opposed to saving money. Developing extension-based programs that involve regular and interactive meetings with growers may significantly increase the adoption of IRM and related integrated pest management tactics.